Partisanship is as ingrained into the political fabric of this country as are the imported core ideologies from whence it sprang. The history of our domestic partisanship can be traced to the days of George Washington’s presidency with the establishment of the Federalist Party (led by Alexander Hamilton – being in favor of a strong federal government) and the Jeffersonian Republicans, which under Thomas Jefferson’s leadership advocated for strong state governments.

Partisanship is as ingrained into the political fabric of this country as are the imported core ideologies from whence it sprang. The history of our domestic partisanship can be traced to the days of George Washington’s presidency with the establishment of the Federalist Party (led by Alexander Hamilton – being in favor of a strong federal government) and the Jeffersonian Republicans, which under Thomas Jefferson’s leadership advocated for strong state governments.

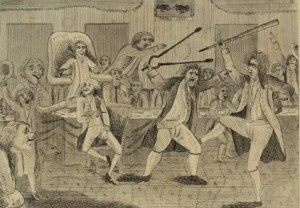

And our history is replete with examples where the individual and collective passions of partisanship have led to bitter conflict, even being manifested in physical assaults on the floors of both houses of Congress.

Shown below is a cartoon depicting a fight in the House of Representatives between Republican Matthew Lyon and Federalist Roger Griswold as depicted in this 1798 engraving. Lyon was the first member of Congress to have an ethics violation charged filed against him when he was accused of “gross indecency” for spitting in Griswold’s face (Griswold had called Lyon a scoundrel, considered profanity at the time). And in 1856, at the heyday of debate over slavery, South Carolina Senator Preston Brooks – deeply agitated at what he considered Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner’s libelous characterization of Brooks three days earlier in his infamous, “Crime Against Kansas” speech (at which Brooks was not present to protest) – used a metal cane to pummel Sumner, who had to be carried off the Senate floor.

And in 1856, at the heyday of debate over slavery, South Carolina Senator Preston Brooks – deeply agitated at what he considered Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner’s libelous characterization of Brooks three days earlier in his infamous, “Crime Against Kansas” speech (at which Brooks was not present to protest) – used a metal cane to pummel Sumner, who had to be carried off the Senate floor.  So perhaps, in retrospect, the challenges of partisan politics standing in the way of addressing the nation’s fiscal crisis need to be taken in context. Or do they?

So perhaps, in retrospect, the challenges of partisan politics standing in the way of addressing the nation’s fiscal crisis need to be taken in context. Or do they?

This morning, the Bipartisan Policy Center hosted a town hall meeting facilitated by USA Today’s Washington Bureau Chief Susan Page at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library to launch the Commission on Political Reform. Beginning today, the 30-member commission will be holding forums across the country in the hope of engaging a body politic unwittingly caught up in the maelstrom of political polarization that has been exacerbated and capitalized upon by a Media that serves a profit motive first and civic responsibilities somewhere south of fifth.

Take this, for example. In advance of the new Commission’s launch USA Today recently conducted a clever – albeit devious – poll in which it surveyed 1,000 individuals who were asked to assess two education polices: the first plan would reduce class sizes and make sure schools teach the basics; the second plan would increase teacher pay while making it easier to remove underperforming teachers.

Half of the respondents were told the first plan was a Democratic plan and the second a Republican plan. For the other half of respondents, the labels were reversed. In both instances, respondents overwhelmingly (by a margin of 3 to 1) favored the plan that was associated with their party affiliation. In fact, both sets of respondents were inclined to describe their support as being “strongly” in favor, regardless of which policy was represented.

The BPC’s President, Jason Grumet, in introducing this morning’s town hall panel was deliberate in noting the Commission’s purpose is not to create Kumbaya symmetry wherein political discourse becomes an effort to go along in order to get along. To the contrary, robust debate is needed now more than ever – because the complexity and urgency of the challenges facing our nation demand it.

But today, intelligent, productive discourse and debate is buried in sound bite rhetoric designed to be easily digested by a society in transit, always seeking first to be entertained – and then thoughtful and concerned. Along with that the tribal instincts of our modern social conscience have made the concept of political compromise tantamount to failure. Since today’s town hall meeting was held at the Reagan Library, I thought it would be fitting to end this post with a quote from President Reagan’s autobiography.

“When I began entering into the give and take of legislative bargaining in Sacramento a lot of the most radical conservatives who had supported me during the election didn’t like it. ‘Compromise’ was a dirty word to them and they wouldn’t face the fact that we couldn’t get all of what we wanted today. They wanted all or nothing and they wanted it all at once. If you don’t get it all, some said, don’t take anything. I’d learned while negotiating union contracts that you seldom got everything you asked for. And I agreed with FDR, who said in 1933: ‘I have no expectations of making a hit every time I come to bat. What I seek is the highest possible batting average.’ If you got seventy-five or eighty percent of what you were asking for, I say, you take it and fight for the rest later, and that’s what I told these radical conservatives who never got used to it.”

Cheers,

Sparky

Charlie Ornstein is a senior reporter at

Charlie Ornstein is a senior reporter at

This post’s title is what I reminded myself of when I read the recent interview Megan McArdle did with Delos (“Toby”) Cosgrove, CEO of the Cleveland Clinic. In that article,

This post’s title is what I reminded myself of when I read the recent interview Megan McArdle did with Delos (“Toby”) Cosgrove, CEO of the Cleveland Clinic. In that article,

A major concern of policy analysts regarding the Affordable Care Act is whether and how the country will be able to produce a sufficient supply of primary care physicians (PCPs) to meet the projected demand arising from extending healthcare coverage. But to what extent future demand for PCP services will be owing to demographics versus expansion in coverage requires the use of some rather subjective assumptions. While it is plausible to assume that removal of cost as an obstacle to healthcare utilization would increase demand among that portion of the population unable to afford coverage, such thinking can also be counterintuitive.

A major concern of policy analysts regarding the Affordable Care Act is whether and how the country will be able to produce a sufficient supply of primary care physicians (PCPs) to meet the projected demand arising from extending healthcare coverage. But to what extent future demand for PCP services will be owing to demographics versus expansion in coverage requires the use of some rather subjective assumptions. While it is plausible to assume that removal of cost as an obstacle to healthcare utilization would increase demand among that portion of the population unable to afford coverage, such thinking can also be counterintuitive. Dr. John Henning Schumann on his blog, GlassHospital. It relates the real life story of a general internist’s experience treating a frail 94-year-old female patient with advanced Alzheimer’s disease and multiple medical issues. It shares the difficult, non-medical oriented challenges that cut a wide swath across the care continuum when dealing with end-of-life care: the patient, her family, the hospital administration, the attending physician and other clinicians at the hospital.

Dr. John Henning Schumann on his blog, GlassHospital. It relates the real life story of a general internist’s experience treating a frail 94-year-old female patient with advanced Alzheimer’s disease and multiple medical issues. It shares the difficult, non-medical oriented challenges that cut a wide swath across the care continuum when dealing with end-of-life care: the patient, her family, the hospital administration, the attending physician and other clinicians at the hospital.

The core challenge is in the one size fits all model of healthcare that currently exists. The system as a…

Reblogged this on rennydiokno.com.

I think you're absolutely right, Scot. We've passed the point of no return on Federal dysfunction.

It sounds like violence can change one's mind about what is right and what is wrong. I always thought that…

The important issue is not the comment that Gruber made rather the fact that he and the administration intended to…