Research published today in the New England Journal of Medicine – Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States – describes the projected economic consequences of caring for an aging population afflicted with various forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease.

Research published today in the New England Journal of Medicine – Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States – describes the projected economic consequences of caring for an aging population afflicted with various forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease.

Separating the caregiving related costs attributable to dementia is challenging, if not impossible, because of the prevalence of comorbidity in individuals having dementia and because of the lack of quantifiable data reflecting the financial burden associated with informal caregiving. Using data from the University of Michigan’s Health and Retirement Study, the study’s authors sought to adjust for such phenomena by parsing out data that is believed to reflect the marginal costs associated with dementia.

Their methodology looked at how these costs could vary over the spectrum of probability within a given population that an individual would be afflicted with dementia. Costs were stratified according to:

Out of Pocket Spending

Spending by Medicare

Net Nursing Home Spending

Formal and Informal Homecare

If the intuitive concern that the economic impact of an aging society will be dramatic, the aggregate cost projections from this research certainly reinforces that concern. With a prevalence rate of 14.7% of the US over the age of 70 having dementia, the current (2010) cost of care (not including the valuation of informal caregiving) is $109 billion. By 2040, if prevalence rates and utilization of non-informal services and care are held constant, that amount is projected to more than double.

The authors note that dementia is one of the most costliest diseases to society, yet 75% to 84% of attributable costs of dementia are related to institutional care (e.g., a nursing care facility) or home-based long-term care – i.e., as opposed to medical care. Healthcare providers in that space should recognize the challenges and opportunities of that consequence.

I think it is important to remember that the inherent subjectivity of the dataset – and the data elements represented – is a reality that cannot be overlooked. In addition, even if there wasn’t the inherent subjectivity, I’m not really sure of the article’s value, nor whether it is deserving of the attention received in the press. Perhaps there’s something there I missed.

Counting the number of teeth a shark has and noting their regenerative capabilities is a fascinating exercise, but it’s the shark that can kill you – not its teeth.

Cheers,

Sparky

Special Note: last summer I shared with Pub visitors a webinar, Emerging Trends and Drivers in Dementia Care, presented by my Artower colleague, Lori Stevic-Rust, PhD ABPP, Board Certified Clinical Health Psychologist and nationally recognized authority on Alzheimer’s disease. Another plug here seems appropriate.

The topic of Hospital Readmissions has evolved into a primary point of discussion and debate within the nation’s lexicon of Healthcare Reform, most notably through broadly accessed media outlets not typically associated with in-depth reporting on medicine and healthcare. As often happens, by the time such a topic traverses the tipping point of being newsworthy it will have actually been around for quite a while in smaller though certainly no less important academic circles.

The topic of Hospital Readmissions has evolved into a primary point of discussion and debate within the nation’s lexicon of Healthcare Reform, most notably through broadly accessed media outlets not typically associated with in-depth reporting on medicine and healthcare. As often happens, by the time such a topic traverses the tipping point of being newsworthy it will have actually been around for quite a while in smaller though certainly no less important academic circles.

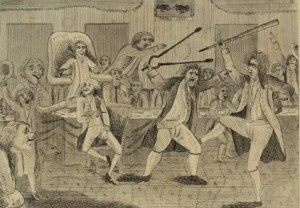

So perhaps, in retrospect, the challenges of partisan politics standing in the way of addressing the nation’s fiscal crisis need to be taken in context. Or do they?

So perhaps, in retrospect, the challenges of partisan politics standing in the way of addressing the nation’s fiscal crisis need to be taken in context. Or do they? Charlie Ornstein is a senior reporter at

Charlie Ornstein is a senior reporter at

The core challenge is in the one size fits all model of healthcare that currently exists. The system as a…

Reblogged this on rennydiokno.com.

I think you're absolutely right, Scot. We've passed the point of no return on Federal dysfunction.

It sounds like violence can change one's mind about what is right and what is wrong. I always thought that…

The important issue is not the comment that Gruber made rather the fact that he and the administration intended to…