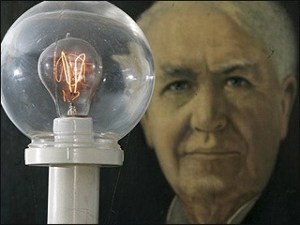

One might think the graphic accompanying this post was leaked from Sen. Ted Cruz’s political strategy playbook: the next chapter in The Tea Party’s Fight to Repeal the Affordable Care Act. It’s not. Could be though, right? The metaphor holds of doing something foolish to gain popular attention and then suffering the individual consequences of that foolishness.

One might think the graphic accompanying this post was leaked from Sen. Ted Cruz’s political strategy playbook: the next chapter in The Tea Party’s Fight to Repeal the Affordable Care Act. It’s not. Could be though, right? The metaphor holds of doing something foolish to gain popular attention and then suffering the individual consequences of that foolishness.

Of course, Tea Party advocates will no doubt claim I am being foolishly satirical and hypocritical for not recognizing my own ignorance in understanding the dramatic importance of standing up for liberty, fiscal responsibility and apple pie. If they truly believe those were Senator Cruz’s motivations, well then what can I say – they must see a political reality in this country different than the one I see.

Even if we were to believe the efforts of Senator Cruz and other Tea Party congressional enthusiasts – to hold the country fiscally hostage for over two weeks in an effort to defund the ACA – were nonpolitically motivated, the overall reaction of the American public can hardly be what they were hoping for. According to a Pew Research Center poll released yesterday, the Tea Party is less popular than ever, even among many Republicans, with nearly half (49%) of survey respondents having an unfavorable opinion. This is up from 37% in June of this year.

On the other hand, Senator Cruz’s popularity among Tea Party respondents has risen from 47% to 74% since July. I’m not sure how well that bodes for his future political aspirations (at least outside of Texas, if that was of interest), but I am being sincere when I say that I respect the all-in approach of any elected official because it represents a refreshing departure from governing by opinion polls.

My view of the Tea Party, for better or worse, is largely based on the individuals I know personally who are either sympathetic to, intellectually aligned with or proud to be members. I find them to be generally well informed on political issues and passionate about protecting individual liberties. Things go downhill when we start debating who gets to define which liberties should be protected and by whom, which I interpret as the Tea Party being discerningly different than many Libertarian viewpoints.

They are very concerned – and I think rightly so – with the economic future of our country and seem to understand more than most that both political parties are guilty of sustaining special-interest budgeting despite whatever expressions of concern we may hear to the contrary. That’s where a large part of the inherent challenge to the Tea Party’s future lies. As shown in the Pew Research poll, there is a lot of confusion, disagreement and debate over whether and how well the Tea Party “fits” within the Republican Party.

I personally hope it finds its national voice apart from the GOP. If it has something meaningful to offer in the nation’s political discourse – it could hardly do worse – then it should seek to do so through the existing construct of our democracy and not by resorting to Machiavellian tactics whereby it seeks to bend the will of a majority to its beliefs (again, I refer you to the Pew Research poll).

I admit, there is a real attraction to a grass roots political movement in an age where electoral helplessness – whether learned or systemic – has become anathema to a democratic form of government. But waxing nostalgic for the 18th century and expecting that same apathetic electorate to embrace the social and cultural norms of men in wigs and women in hoops is a very tough sell.

And that’s where I find the greatest difficulty in accepting my Tea Party colleagues’ personal political platform. To me it feels like hidden below the surface of, “strike a blow for liberty,” “defend the Constitution” and “balance the budget” is an observable pattern in their logic and debate that belies a commiserate longing for the good old days.

I think all of us over a certain age find ourselves quite often reflecting on a past that was less stressful, less fearful, less threatening and certainly less complicated. Today we live in a world of constant change that just one generation removed couldn’t possibly have imagined. In his book, Managing at the Speed of Change, Daryl Conner talks about the Beast: a metaphor of the challenge each of us faces in adapting to constant change in our environment. It takes incredible resiliency to maintain good mental health in the 21st century.

I do not believe effective public policy – including Healthcare policy – can or should be based on what worked in the good old days. As Don Henley wrote, “those days are gone forever – [we] should just let ‘em go but…” Today we live in a society that is aging at an accelerated rate, that is growing in ethnic and cultural diversity and is inundated on a 24-7 basis with technological advancements that introduce hope and terror in equal measures.

With that understanding of reality, my primary concern with the Tea Party is the perceived sense of moral intransigence and impractical political dogma that transcends their beliefs. We should be focusing our efforts on how best to practically adapt a constitutional style of government to the world we live in today – not expecting today’s society to mirror that of the 1700s. I think I share just as much angst and anxiety over our nation’s future as do my Tea Party colleagues. I just don’t believe that going backwards offers much hope in addressing the problems we face today and tomorrow.

Cheers,

Sparky

The title of this post is a reminder to myself and not intended to offend the millions of other participants in healthcare to whom its application may or may not apply. I remind myself of this assertion quite often – primarily because I believe it provides the singular most important connection between the practice of healthcare and the business of healthcare. It also has the theoretical advantage of transcending many of the political realities of public policy because it reinforces commonly held beliefs regarding individual liberties, morality, as well as social consciousness.

The title of this post is a reminder to myself and not intended to offend the millions of other participants in healthcare to whom its application may or may not apply. I remind myself of this assertion quite often – primarily because I believe it provides the singular most important connection between the practice of healthcare and the business of healthcare. It also has the theoretical advantage of transcending many of the political realities of public policy because it reinforces commonly held beliefs regarding individual liberties, morality, as well as social consciousness.

Today is World Alzheimer’s Action Day. And this past week Alzheimer’s Disease International issued,

Today is World Alzheimer’s Action Day. And this past week Alzheimer’s Disease International issued,

have to begin complying with ACA reporting requirements until 2015 (a year delay), she responded, “no – absolutely not. I don’t think it’s virtuous at all. In fact, the point is, is that the mandate was not delayed. Certain reporting by businesses that could be perceived as onerous — that reporting requirement was delayed, partially to review how it would work and how it could be better. It was not a delay of the mandate for the businesses, and there shouldn’t be a delay of the mandate for individuals.”

have to begin complying with ACA reporting requirements until 2015 (a year delay), she responded, “no – absolutely not. I don’t think it’s virtuous at all. In fact, the point is, is that the mandate was not delayed. Certain reporting by businesses that could be perceived as onerous — that reporting requirement was delayed, partially to review how it would work and how it could be better. It was not a delay of the mandate for the businesses, and there shouldn’t be a delay of the mandate for individuals.”

article,

article,

The core challenge is in the one size fits all model of healthcare that currently exists. The system as a…

Reblogged this on rennydiokno.com.

I think you're absolutely right, Scot. We've passed the point of no return on Federal dysfunction.

It sounds like violence can change one's mind about what is right and what is wrong. I always thought that…

The important issue is not the comment that Gruber made rather the fact that he and the administration intended to…